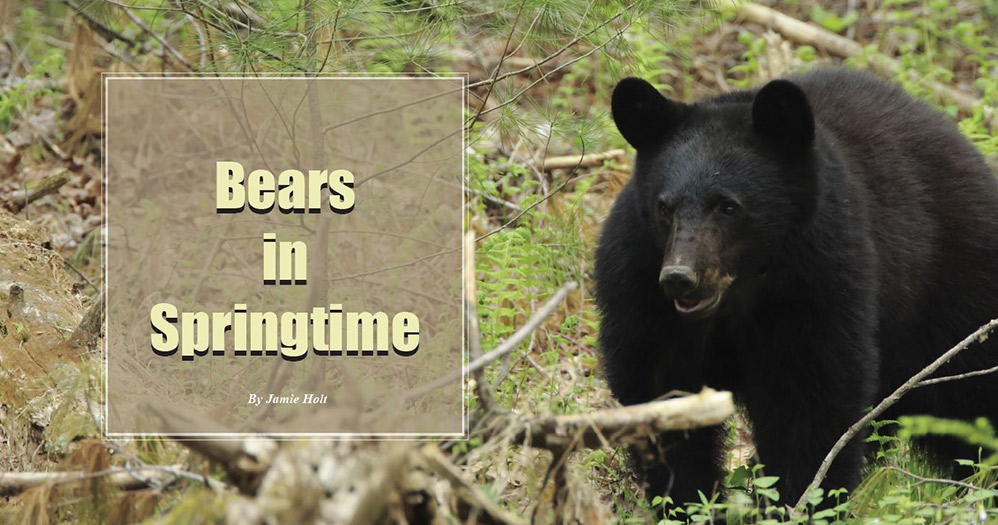

Bears in Springtime

3/9/2018 10:25:12 AM

By Jamie Hold, MDWFP Black Bear Biologist

Throughout most of the 20th century, a black bear in Mississippi has been little more than a distant memory derived from stories passed down from one generation to the next, fueled by the occasional coffee shop talk of a sighting.

Pre-1900, Mississippi was home to one of the densest populations of black bears in the country. Because of habitat destruction and over-harvest, black bears in Mississippi became that story of what used to be. Then things began to change.

As a whole, society became mindful of the direct, cause-and-effect relationship we have with our natural resources. With the aid of government programs, conservation-minded landowners have worked hard the last few decades to reconstruct and con-serve wildlife habitat across the state. But what benefits do we now see from the years of work and millions of dollars that have gone into habitat restoration and wildlife conservation? One of these benefits is the recolonization of black bears in the state. Over the last two decades, the black bear population has in-creased to an estimated 200 statewide. So, how did this happen?

Mississippi has multiple success stories involving wildlife that were pushed to dangerously low population numbers. Some successes, such as the white-tailed deer and eastern wild tur-key, are widely known and well-appreciated by outdoor enthusiasts. Much of this success was because of the state wildlife agency and cooperating landowners restocking the entire state and letting the population build from there. Bears, however, are a much different story.

In 1934, the state released six bears in a restocking effort, but none survived. Sixty years later, bear sightings became a little more than hearsay. While most of these sightings were males passing through, it was a step in the right direction. However, no amount of boars (male bears) moving through an area will have a long-term effect on a population without one key com-ponent: sows (female bears). As chance would have it, things soon changed again. As populations in adjacent states expanded, sows began to swim the Mississippi River from Arkansas and Louisiana into the state. Most importantly, those sows established home ranges and began to breed. These events were the turning point for black bears in Mississippi. Even today, we continue to watch one of Mississippi’s few natural success stories being written. No one knows what made the bears start migrating into Mississippi, but fortunately the habitat they found made them stay.

Like any wildlife species, one of the major biological requirements for each individual is space. As population density increases in an area, the need to expand into new areas becomes essential. As in many species, gender is the main factor that will dictate how far an individual will travel. Female cubs generally remain close to the area where they were born and raised, while males have been known to move hundreds of miles in search of a place to call home. Many other factors, such as habitat quality and seasonal food supply, also play a large role in this home-range selection.

Like any wildlife species, one of the major biological requirements for each individual is space. As population density increases in an area, the need to expand into new areas becomes essential. As in many species, gender is the main factor that will dictate how far an individual will travel. Female cubs generally remain close to the area where they were born and raised, while males have been known to move hundreds of miles in search of a place to call home. Many other factors, such as habitat quality and seasonal food supply, also play a large role in this home-range selection.

Many people associate bears and winter with hibernation. However, black bears in Mississippi do not go into a true hibernation. Instead, they exhibit a behavior called carnivorean lethargy or torpor; commonly referred to with black bears as denning. Torpor is a dormancy period that allows bears and other carnivores to survive low food supplies and inclement winter weather. In the southern United States, this period is more often associated with flooding than cold. Sows also use this time of year to give birth to young. This time in the den gives the cubs opportunity to strengthen and grow before emerging in the spring.

Spring is an essential time for black bears. After surviving the winter with little to no food, it is now time to take advantage of the lush green vegetation that is engulfing the landscape. Thanks to an inefficient digestive system and an average diet of 90 percent vegetation, bears spend a significant amount of time in search of food.

Bear activity and movement change throughout spring, summer, and fall in response to seasonal food availability. With adult body weights ranging from 200 to 400-plus pounds, large amounts of food are needed for bears to thrive in the wilderness. Bears moving around the landscape in search of food increases the chances of human interaction. Inevitably, increased human/bear interaction results in conflict on some level. Why does this conflict occur? It comes back to food, but let us first discuss more about black bear feeding behavior.

Black bears are opportunistic omnivores, which means they will eat almost anything they happen upon. When it comes to foraging, bears are downright lazy creatures. Often compared to raccoons, bears will take advantage of easy meals. This includes household garbage, pet food, carrion (dead animals), and wildlife/bird feeders. Bears are brilliant animals and not only have an extraordinary ability to learn, but also have a memory to match. Therefore, when bears find those easy meals, they remember where the food sources are and will continue to exploit these sources until no longer available. The best way to avoid or stop these conflicts is to remove the attraction, which could include installing an electric fence around a garden, reinforcing garbage cans and adding latches, or eliminating wildlife/bird feeders.

Some refer to bears as an all-around “nuisance,” when in fact we often entice this behavior by leaving food items easily accessible to bears. Other states in the eastern U.S. have black bear populations as high as 30,000 individuals. Mississippi residents and sportsmen are just as able to live in a state with bears as those from Pennsylvania and Maine. The key difference is this is something new for Mississippi. We are not accustomed to bear-proofing our homes and hunting camps where residents of other states have never known otherwise. Sharing the land with bears should not be looked at as an obstacle but an adjustment in our habits. Everyone needs to understand that there is comfortable common ground to be had with this large, charismatic megafauna.

Some refer to bears as an all-around “nuisance,” when in fact we often entice this behavior by leaving food items easily accessible to bears. Other states in the eastern U.S. have black bear populations as high as 30,000 individuals. Mississippi residents and sportsmen are just as able to live in a state with bears as those from Pennsylvania and Maine. The key difference is this is something new for Mississippi. We are not accustomed to bear-proofing our homes and hunting camps where residents of other states have never known otherwise. Sharing the land with bears should not be looked at as an obstacle but an adjustment in our habits. Everyone needs to understand that there is comfortable common ground to be had with this large, charismatic megafauna.

Many times people ask, “Why do we need black bears back in Mississippi with all the potential problems associated with them?” The simple answer to that question is this: for the same reason we needed restoration of the white-tailed deer, eastern wild turkey, American alligator, and American beaver. While almost any wildlife species can present wildlife/human conflict one situation or another, they are all a significant part of the natural resources we hold dearly. Everything in nature is connected to some degree and survival of all species is dependent on maintaining the balance between them. To consider one species or resource as more important than another is the same mentality that destroyed wildlife populations and habitat across the country. We have made leaps and bounds in correcting those mistakes made many years ago. We understand the true meaning of being good stewards of the environment, to ensure these resources thrive for many years to come.

We all play an integral role in natural resource management. We fill a broad range of duties with many titles: hunters, an-glers, caretakers, biologists, foresters, bird watchers, and out-door enthusiasts. But, we all have the same objective, and we are all conservationists.

Jamie Holt is a Black Bear Program Biologist for the MDWFP.