Beyond the Swamps

8/12/2019 4:09:57 PM

By Ricky Flynt

Alligators have existed in Mississippi for tens of thousands of years, and, according to fossil records, alligators and crocodiles are probably the closest living creature to a dinosaur still in existence. Their pre-historic appearance is partly responsible for the fear most people have when they come in close contact with one. The secretive behavior, protective bony covering on its back, and powerful jaws and tail demand respect by all creatures within its environment, including man.

The American alligator boldly sits at the top of the food chain in southeastern wet-lands, and no other North American creature challenges it for that position. However, because of over-harvest and lack of conservation regulations, alligators be-came in danger of being forever removed from the food chain in the early to mid-1900s. Markets for its durable and exotic hide from the 1890s–1960s brought about action from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), which placed the American alligator on the Endangered Species List throughout its entire south-eastern United States range in 1967.

Following its endangered listing, stiff penalties curtailed illegal alligator harvest and, amazingly, populations recovered more quickly than anticipated. In 1987, its status was changed to “threatened” because of similarity of appearance, which allows wildlife officials to identify alligator parts from other endangered crocodilians entering commercial trade. Shortly after that, people in alligator markets began experimenting with farming alligators, and commercial alligator farming was successfully created in Louisiana and Florida, with regulation oversight from the USFWS and state wildlife agencies.

Now, after years of research and closely regulated monitoring, alligators can be commercially raised from an egg to marketable sizes of 42-48 inches in 10–14 months. In the wild, growth rates are much slower and can take 4–6 years to reach such marketable sizes. The alligator farming business in Louisiana is annually a multi-million dollar commercial operation with global impacts on alligator products. Thus, alligator farming has provided resources to commercial markets that have contributed significantly to reducing the illegal harvest of wild alligators.

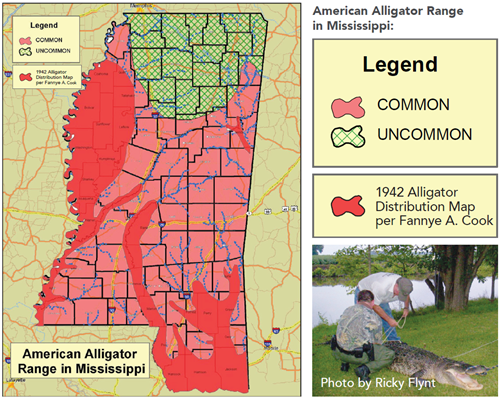

Mississippi’s alligator population during this time was impacted severely by habitat destruction and overharvesting. According to journal entries by Fannye A. Cook, who founded the Mississippi Game and Fish Commission in 1933, alligators were primarily located in the lower Mississippi River floodplain, on the Yazoo, Big Black, Pearl, Leaf, and Pascagoula rivers. To re-store Mississippi’s alligator population after it was placed on the Endangered Species List, the Game and Fish Commission relied heavily upon the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. From 1970–1978, approximately 4,000 alligators were captured from the Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge in Grand Chenier, Louisiana, and transported to Mississippi. Most relocated alligators were less than 4 feet long, but occasionally alligators over 8 feet long were released. At the time, Mississippi landowners could request the release of alligators on their property in hopes of controlling snakes, turtles, and beaver. Annually, pick-up trucks and, occasionally, 18-wheeler trailers were loaded with captured alligators destined for relocation in Mississippi.

Carl Mason, who is now retired from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, released alligators in Neshoba County and the Noxubee National Wildlife Refuge in 1970 as part of a Mississippi State University research project to study how effective alligators could control existing beaver populations. Mason, a Mississippi State wildlife and fisheries graduate student at the time, released alligators and beaver together in large holding pens and observed them daily. The smallest alligator released was 6 feet long, but most were longer than 8 feet. According to Mason, it did not take long to realize that alligators and beaver would coexist. He noted that if an alligator’s jaws did not get a firm hold of an adult-sized beaver’s head, then the alligator received vicious biting and swift kicks from the beaver. Alligators soon learned to avoid larger beaver and only occasionally preyed upon young beaver. These research results took “wind out of the sails” of biologists who hoped to use alligators as a natural method to control increasing timber damage caused by beaver.

The Mississippi Game and Fish Commission’s relocation efforts, combined with federal regulations protecting alligators, allowed the alligator population in Mississippi to rebound. In some cases, alligators rebounded beyond expectations into areas where they were not common before being listed as endangered. A statewide survey of conservation officers in 1977 indicated that alligators occurred in 55 of 82 counties. A similar survey in 2006 reported an increase to 77 of counties with alligators.

As alligator populations recovered and continued to grow in the Southeast, hunting has become a useful tool for population management. Louisiana began its first alligator hunting season in 1972 and has since been joined by Florida (1981), Texas (1984), Georgia (2003), Mississippi (2005), Alabama (2006), Arkansas (2007), and South Carolina (2008), and North Carolina is considering its first gator season for 2020. This expansion of alligator hunting opportunities has been equaled by huge growth in hunter interest. Mississippi’s 2019 season begins at noon Aug. 30 and concludes at noon Sept. 9 for public waters; at 6 a.m. Sept. 23 for private lands.

When Mississippi initiated its first alligator hunting season in 2005, opportunities were minimal. A 16-mile section of the Pearl River north of Ross Barnett Reservoir was opened to 50 lottery-based permits. There were over 1,200 applications submitted by Mississippi residents who hoped to participate in this inaugural opportunity. By 2007, alligator hunting season expanded to two hunting zones, the Pearl River/Ross Barnett and Pascagoula River Zones, with 240 available permits. By 2013, public water hunting opportunities were offered statewide with 920 available permits. Private lands alligator permit opportunities have grown from seven open counties in 2008 to 36 counties in 2019. There were 117 properties that qualified for permits in 2018.

Alligator hunts in Mississippi have been successful for many reasons, one of which was requiring a mandatory alligator hunting training course for all permittees from 2005 until 2014 (more than 5,000 participants). Since 2015, the training course has become voluntary. The course includes four training hours on alligator history, bi-ology, alligator research, capture and harvest methods, harvest tagging and reporting, skinning and processing instruction, and hunting and boating safety. Anyone who has completed the course will attest to the value of such training before pursuing and handling such an intimidating creature.

Alligators are an integral part of wetland ecosystems in the Southeast. Their resurgence from almost extinction is one of the true wildlife conservation success stories of the 20th century, as well as a testament to the importance of wildlife conservation laws. Since alligators are now prevalent throughout the Southeast again, these populations are managed as a renewable resource through sustainable, regulated harvest by hunters throughout its range.

As Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks’ (MDWFP) Alligator Program continues to grow, alligator hunting opportunities continue to expand each year. For 2019, there are 960 public water hunting permits and 36 counties open to private lands hunting applications. For more information on alligators or alligator hunting and the application process, please visit www.mdwfp.com/alligator.

Ricky Flynt is the MDWFP Alligator/Furbearer Program Coordinator.