Chronic Wasting Disease: Present, Past, and Future

3/22/2018 2:11:33 PM

By William T. McKinley, MDWFP Deer Program Coordinator

In February, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Veterinary Services Laboratory confirmed the first positive Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) test for a sample collected from a deer within Mississippi.

A hunter witnessed the infected animal, a 4-year old buck weighing only 96 pounds, die from secondary pathogens as a result of the disease on January 21. An MDWFP biologist collected the specimen on January 25 and the MDWFP received the results of the CWD test on February 9, the same day information about the detection of the disease in Mississippi was released to the public.

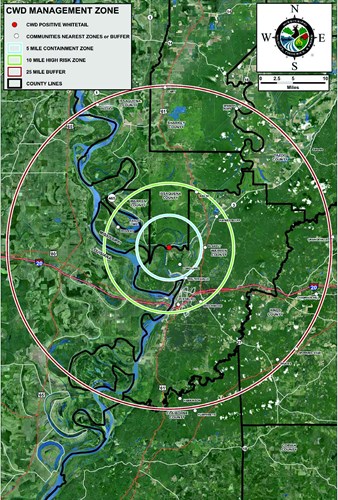

CWD Management Zone

click to enlarge

Upon notification of detection, the MDWFP enacted our CWD Response Plan, which can be found on the MDWFP website at www.mdwfp.com/cwd. As part of the plan, the MDWFP established a Containment Zone, a High-Risk Zone, and a Buffer Zone in concentric circles with a 5-, 10-, and 25-mile radius, respectively, around the area where the infected deer was collected. Within each zone, the MDWFP will collect samples based on a protocol outlined in the plan. The primary goal of the initial sampling effort is to define the geographic extent and prevalence of the disease. The results of these initial sampling procedures are critical to informing and adapting our management strategy for the disease in the region. The MDWFP will continue to update the public as more information becomes available and the appropriate strategy is formulated.

What is CWD?

CWD is a contagious, prion disease that is known to affect the following members of the deer family (cervids): white-tailed deer, elk, mule deer, sika deer, moose, and reindeer. CWD appears to be caused by one or more strains of infectious prions, which researchers have identified as an abnormal protein. The theorized origin of CWD is exposure of native cervids to the sheep scrapie agent at one or more times and locations. The first case of CWD was described in a captive mule deer population in Colorado in 1967. It may take more than a year before an infected animal develops symptoms, which can include drastic weight loss (wasting), stumbling, listlessness, and other neurologic symptoms.

There is no treatment for the disease, no vaccination for prevention, no practical live animal test to determine if an animal is infected, and no way to test processed venison to determine contamination. Laboratory analysis of the brain and/or the retropharyngeal lymph nodes of a dead animal is the only method currently accepted by the USDA as conclusive. Once this dis-ease occurs in an area, past evidence demonstrates that it will not go away on its own—aggressive intervention is required to manage the impact.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there have been no reported cases of CWD infection in people. However, animal studies suggest CWD poses a risk to some types of non-human primates, like monkeys, that eat meat from CWD infected animals or come in contact with brain or body fluids from infected deer or elk. These studies raise concerns that there could be a risk to people. Since 1997, the World Health Organization has recommended that it is important to keep the agents of all known prion diseases from entering the human food chain.

Prions associated with the disease are found throughout the body of infected animals but are found in higher concentrations in the eyes, lymph, and nervous tissues. Infected animals shed prions through saliva, feces, blood, and urine. Other animals can become infected through direct contact with an infected animal and indirect contact with an infected environment. Research has shown that decomposed carcasses of infected animals can also contribute to transmission. Plants can bind prions superficially and uptake prions from contaminated soil, resulting in possible infection to the animal eating the plant. Prions in the environment are found to be more infective in particular (clay) soil types. There is no known method to decontaminate an infected environment.

As of February, Mississippi is the most recent of 25 states (78 captive herds in 16 states and free-ranging cervids in 23 states) to detect the disease, which also has been confirmed in three Canadian provinces, Norway, and South Korea.

Spread of the Disease

Much of the geographic spread of CWD in some areas likely is because of natural movements such as dispersal and migration. The disease could incubate for years, all the while the animal is shedding prions and thus infecting an environment. Artificial management activities that congregate animals, such as baiting and feeding, increase the opportunity for disease transmission. Thus, per Mississippi’s CWD Response Plan pursuant under the Order of the MDWFP Executive Director on behalf of the Commission, supplemental feeding has been banned in the following counties: Claiborne, Hinds, Issaquena, Sharkey, Warren, and Yazoo.

The primary means of spread of CWD over distant locations is believed to be the human-facilitated movement of diseased live animals. In many cases (Missouri, Oklahoma, New York, and others), movement of infected animals has been associated with captive animal facilities. Since 2013, seven individuals have been convicted of violations of the Lacey Act for importing live white-tailed deer into high-fenced enclosures in Mississippi. More than 150 live white-tailed deer were in these shipments. These deer originated from six states, four of which have confirmed CWD within their borders. One shipment contained imported deer from facilities in Pennsylvania that were subsequently quarantined because of exposure to CWD positive deer.

Other possible means for humans to spread CWD over long distances include:

- transport of infected carcasses

- products manufactured or contaminated with prion-laden deer or elk urine, saliva, or feces

- movement of hay or grain crops contaminated with the CWD agent

These routes of transmission have been demonstrated experimentally, but have not been confirmed in the field. Mississippi has enacted laws to help protect our deer herd from further spread of CWD. Importing live CWD-susceptible cervids into the state is illegal. It is illegal to transport certain portions of a cervid carcass into Mississippi from states that have discovered CWD. In-state transportation of carcasses from within the CWD Buffer Zone will also be restricted.

Statewide Monitoring and Surveillance

In addition to intensive sampling within the CWD Management Zones, the MDWFP will increase our current surveillance efforts in other areas of the state. In 2015, based on research from areas where CWD had been detected, the MDWFP shifted the focus of our CWD surveillance from hunter-harvested animals to reported animals with clinical symptoms, roadkill, and samples from cooperating taxidermists (to gain older-age bucks) to increase our likelihood of detecting diseased animals if present. The agency is currently working on a protocol to make testing of hunter harvest animals available, statewide.

William T. McKinley is the Deer Program Coordinator for the MDWFP.