- Log in to post comments

6/18/2019 9:13:56 AM

By Russ Walsh

My dad whispered these words to me on a crisp, October morning squirrel hunt many years ago. On this morning, he was teaching my brother and me how to quietly (a relative term for two boys) and judiciously navigate the squirrel woods. My love of hunting, like many of you, began with the pursuit of small game. Other hunts and lessons would follow that would foster a lifelong passion for the outdoors.

I am grateful for a father who shared his love of hunting with his sons. With the passing of time and gathering of knowledge, I have learned to be especially grateful for the mere opportunity to pursue wild critters in wild places. In the United States, we all benefit from a wildlife conservation model that is unmatched. Our fascinating history of hunting and wildlife conservation is certainly too long for this brief article, but I trust it will pique your interest and prompt you to delve further into our storied heritage.

EARLY TIMES

During America’s early years, European colonists were still accustomed to wildlife and land being owned by the king. Hunting had been reserved for the upper class, often by invitation only. Many had never enjoyed partaking in the rich heritage of pursuing wild game. With the founding of America came many new freedoms, including the opportunity to hunt, fish, trap, and explore nature.

North America boasted abundant natural resources that had sustained the Native American culture for centuries. As the United States grew, resources were needed to build, develop, and expand. By the late 1800s, an increasingly urbanizing society had a demanding need for food and fur. The advent of railways allowed market hunters to expeditiously transport the hides and meat of bison and other big game. Westward exploration fueled these markets, further exploiting timber, land, and wildlife.

The largely unfettered hunting of many game species would eventually lead to overharvest, leaving many species dangerously close to extirpation or, at worst, extinction. As the turn of the century loomed, those who had a strong passion for nature took notice and demonstrated a deep concern for its future. President Theodore Roosevelt’s love of wild places forged a deep conviction for conserving America’s resources for future generations. Roosevelt stated, “There is a delight in the hardy life of the open. There are no words that can tell the hidden spirit of the wilderness that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy and its charm. The nation behaves well if it treats the natural resources as assets, which it must turn over to the next generation increased and not impaired in value.”

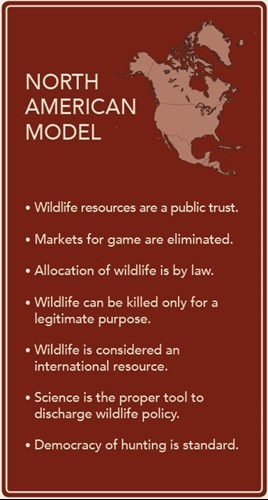

The great democracy that allowed over-exploitation would, ironically, also allow active engagement in the conservation movement. Many iconic figures involved in the process would arise during this era, leaving indelible marks on conservation. A common collection of principles guided the individuals shaping early conservation efforts. These basic tenets, coupled with existing laws, are the underpinnings for what is now known as the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. Seven components of the Model are:

Wildlife resources are a public trust: Court decisions had established that wild-life was to be held by the government in public trust for the citizenry. This essential basis is known as the Public Trust Doctrine and is the foundation for state and federal wildlife agencies that exist today. The core concept of this law would ensure access to resources for hunting and fishing—an opportunity for all.

Markets for game are eliminated: Unregulated market hunting of birds and game in the 19th century led to marked population declines. Thus, the abolition of markets for these animals was a critical step for stopping, or at least slowing, the fall. Some fur markets remain, but they are regulated and monitored to ensure population sustainability.

Allocation of wildlife is by law: Basic laws ensured access to wildlife for all citizens rather than being based on social class, land ownership, or another conditional status. This principle also allows for public involvement in the development of laws that govern natural resource conservation.

Wildlife can be killed only for a legitimate purpose: This principle was derived from those strongly believing in fair chase and no commercial use or wasting of harvested game.

Wildlife is considered an international resource: Conservationists recognized certain wildlife species, particularly birds, migrate across international borders. Thus, an individual nation’s management of certain species may have global consequences. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 is a successful example of international collaboration to ensure bird conservation.

Science is the proper tool to discharge wildlife policy: Scientific research of wildlife and their ecosystems is critical for informed decision making. Sound policy must be rooted in rigorous scientific findings. Myriad natural resource institutions across the country have not only produced valuable scientific findings but have also trained skilled wildlife professionals.

Democracy of hunting is standard: Hunting and fishing opportunity and access for all is foundational to the public trust and is a signature of our democracy.

Over the last two centuries, the Model has led to unrivaled wildlife conservation successes in the United States and Canada.

- Conservation efforts that saved wildlife species from extinction.

- Game populations being abundant and sustainable.

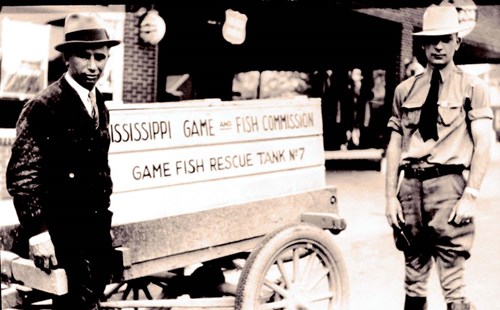

- Establishment of state fish and wildlife agencies that manage the public trust.

- Legal frameworks for establishing seasons and bag limits.

- Establishment of conservation funding mechanisms such as the Pittman-Robertson, Dingell-Johnson, and Duck Stamp acts.

- Wildlife protection laws such as the Endangered Species Act.

- Establishment of millions of acres of public land for recreational use.

GOING FORWARD

Today, there are unique challenges for the Model, and each certainly deserves attention. However, we as hunters, anglers, bird watchers, or general outdoor enthusiasts must be mindful that we continue to benefit from these core principles. Our heritage is dependent upon a firm understanding of the opportunities they afford us.

I am grateful for our conservation predecessors that did not “shuffle their feet;” instead, they took action and formalized a conservation movement to keep wild things wild. I look forward to times afield with my children and sharing the lessons I have garnered through the years. A distinct part of that is passing on the history of our storied hunting and fishing heritage. Perhaps they will develop deep gratitude for our opportunities. And just perhaps, not shuffle their feet.

Russ Walsh is MDWFP’s Executive Officer for Wildlife.