Since the peak infection period occurs when few people spend time in the woods, even severe outbreaks may go unnoticed initially. More commonly, hunters will find carcasses or notice recovering animals during the hunting season. Occasionally, in late summer, someone will observe a sick deer or a carcass in or near water.

Since the peak infection period occurs when few people spend time in the woods, even severe outbreaks may go unnoticed initially. More commonly, hunters will find carcasses or notice recovering animals during the hunting season. Occasionally, in late summer, someone will observe a sick deer or a carcass in or near water.

The observable signs of infection vary with the three forms of HD: peracute, acute, and chronic. The peracute form, characterized by its rapid onset, is the most dramatic. Deer may exhibit a loss of awareness of their surroundings, very high fever, difficulty in breathing, swelling of the head and neck, and the bluish coloration and swelling of the tongue that makes "bluetongue" a common name of the disease. Death from the peracute form often occurs within 24 hours. In especially severe cases deer may die suddenly, even before any observable signs are evident.

With the acute or classic form of HD, deer live somewhat longer. In addition to swelling associated with the peracute form, these animals may show hemorrhaging in the heart, rumen, and intestines. They may also have ulcers on the tongue, dental pad, palate, rumen, and omasum.

With the acute or classic form of HD, deer live somewhat longer. In addition to swelling associated with the peracute form, these animals may show hemorrhaging in the heart, rumen, and intestines. They may also have ulcers on the tongue, dental pad, palate, rumen, and omasum.

Many hunters are familiar with the hoof sloughing associated with the chronic form of hemorrhagic disease because the condition frequently persists into the winter. An interruption of growth, resulting from high fever, often causes the hooves to appear broken or ringed. In extreme cases the tips of the hooves will actually slough off. Debilitated deer may crawl on their knees or even push along on their chest, resulting in additional lesions on those areas. Although less frequently noticed, the lining of the rumen may also become ulcerated, scarred, or even eroded. The deer's ability to absorb nutrients from ingested food is compromised when significant amounts of papillae, the finger-like projections on the rumen wall, are lost. Emaciation can result, even in the presence of ample food resources.

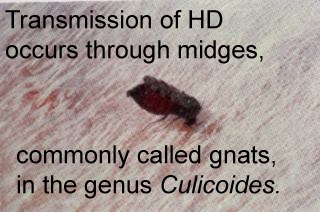

Hemorrhagic disease commonly occurs in 2 forms: epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) and bluetongue (BT). The viruses that cause HD are in the genus Orbivirus. There are two serotypes of EHD virus (serotypes 1 and 2) and six serotypes of BT virus (serotypes 1, 2, 10, 11, 13, and 17) that occur in the United States. All except BT 1 have been found in Mississippi deer.

Hemorrhagic disease commonly occurs in 2 forms: epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) and bluetongue (BT). The viruses that cause HD are in the genus Orbivirus. There are two serotypes of EHD virus (serotypes 1 and 2) and six serotypes of BT virus (serotypes 1, 2, 10, 11, 13, and 17) that occur in the United States. All except BT 1 have been found in Mississippi deer. Since the peak infection period occurs when few people spend time in the woods, even severe outbreaks may go unnoticed initially. More commonly, hunters will find carcasses or notice recovering animals during the hunting season. Occasionally, in late summer, someone will observe a sick deer or a carcass in or near water.

Since the peak infection period occurs when few people spend time in the woods, even severe outbreaks may go unnoticed initially. More commonly, hunters will find carcasses or notice recovering animals during the hunting season. Occasionally, in late summer, someone will observe a sick deer or a carcass in or near water. With the acute or classic form of HD, deer live somewhat longer. In addition to swelling associated with the peracute form, these animals may show hemorrhaging in the heart, rumen, and intestines. They may also have ulcers on the tongue, dental pad, palate, rumen, and omasum.

With the acute or classic form of HD, deer live somewhat longer. In addition to swelling associated with the peracute form, these animals may show hemorrhaging in the heart, rumen, and intestines. They may also have ulcers on the tongue, dental pad, palate, rumen, and omasum. The relationship between deer population density and the rate of occurrence of HD is not fully understood. The disease is not considered to be classically density dependent because the infection rate does not increase directly with the deer population. Obviously, the occurrence and prevalence of the midge vector contribute to the timing and rate of infection. It is logical that the higher the density of the deer herd, the greater the opportunity for the virus to be transmitted from deer to deer via midges.

The relationship between deer population density and the rate of occurrence of HD is not fully understood. The disease is not considered to be classically density dependent because the infection rate does not increase directly with the deer population. Obviously, the occurrence and prevalence of the midge vector contribute to the timing and rate of infection. It is logical that the higher the density of the deer herd, the greater the opportunity for the virus to be transmitted from deer to deer via midges. Experimental infection of deer from northern and southern populations produced markedly different results. Clinical disease was mild or completely absent in the southern deer, while mortality in northern deer was 100% from one strain of the virus and 20% from another. This demonstrates that populations frequently exposed to the viruses apparently develop genetic resistance to HD through the processes of natural selection. Deer that have suffered from the chronic form of the disease develop an immunity to that particular strain of the virus but are still susceptible to the other strains. This immunity can be detected through testing of serum collected during herd health evaluations.

Experimental infection of deer from northern and southern populations produced markedly different results. Clinical disease was mild or completely absent in the southern deer, while mortality in northern deer was 100% from one strain of the virus and 20% from another. This demonstrates that populations frequently exposed to the viruses apparently develop genetic resistance to HD through the processes of natural selection. Deer that have suffered from the chronic form of the disease develop an immunity to that particular strain of the virus but are still susceptible to the other strains. This immunity can be detected through testing of serum collected during herd health evaluations. Nasal bots begin life when the adult fly lays a group of eggs around the nose or mouth of deer. The small larvae within these eggs are released when the deer licks the eggs. The warm, wet saliva creates an environment that permits the "hatching" of the immature bots. These larvae then migrate to the nasal passages and occasionally into the sinuses, where they molt into larger stages of the maturing larvae.

Nasal bots begin life when the adult fly lays a group of eggs around the nose or mouth of deer. The small larvae within these eggs are released when the deer licks the eggs. The warm, wet saliva creates an environment that permits the "hatching" of the immature bots. These larvae then migrate to the nasal passages and occasionally into the sinuses, where they molt into larger stages of the maturing larvae. According to Diseases and Parasites of the White-tailed Deer, published by the Tall Timbers Research Station, R. F. Shope was the first wildlife investigator to actually find the specific virus. Shope was also the first researcher who experimentally infected deer with the viral agent. He found that the fibromas normally appeared at about 7 weeks after inoculation and that they began to regress after 2 months in most deer. Because of his work with infectious cutaneous fibromas, a commonly accepted name for the growths is Shope's fibroma.

According to Diseases and Parasites of the White-tailed Deer, published by the Tall Timbers Research Station, R. F. Shope was the first wildlife investigator to actually find the specific virus. Shope was also the first researcher who experimentally infected deer with the viral agent. He found that the fibromas normally appeared at about 7 weeks after inoculation and that they began to regress after 2 months in most deer. Because of his work with infectious cutaneous fibromas, a commonly accepted name for the growths is Shope's fibroma. Rarely do fibromas cause deer any problems, but occasionally the location of a large single or multiple clump of fibromas can interfere with sight, eating, breathing, or even the ability of the deer to walk. Occasionally, the larger fibromas acquire a bacterial infection through a break in the skin.

Rarely do fibromas cause deer any problems, but occasionally the location of a large single or multiple clump of fibromas can interfere with sight, eating, breathing, or even the ability of the deer to walk. Occasionally, the larger fibromas acquire a bacterial infection through a break in the skin. An array of wart-like viruses also appears on domestic livestock. These viruses are different from the ones found on white-tailed deer; therefore, spreading of the deer fibromas to livestock is considered to be of no consequence.

An array of wart-like viruses also appears on domestic livestock. These viruses are different from the ones found on white-tailed deer; therefore, spreading of the deer fibromas to livestock is considered to be of no consequence. No human infection from cutaneous fibromas has been reported. The only concern for hunters would be from an animal with extensive bacterial infection, which would render the deer unsuitable for human consumption. These animals would be readily apparent due to the unpleasant exudate produced at the infection site.

No human infection from cutaneous fibromas has been reported. The only concern for hunters would be from an animal with extensive bacterial infection, which would render the deer unsuitable for human consumption. These animals would be readily apparent due to the unpleasant exudate produced at the infection site. Chronic Wasting Disease

Chronic Wasting Disease